In the crushing darkness two miles beneath the ocean's surface, where sunlight cannot penetrate and pressures exceed 250 atmospheres, life persists in ways that defy conventional biological wisdom. The discovery of thriving microbial communities around hydrothermal vents has revolutionized our understanding of life's adaptability, particularly through their remarkable ability to perform direct electron transfer. These extremophiles don't just survive in this alien environment - they've developed sophisticated electrical networks that may hold secrets about life's origins and future biotechnological applications.

The hydrothermal vent systems along mid-ocean ridges create bizarre landscapes where superheated, mineral-rich water gushes from chimney-like structures. What appears hostile to most lifeforms - temperatures exceeding 400°C, toxic metal concentrations, and complete darkness - becomes fertile ground for microbial mats that coat the mineral deposits. These microorganisms have evolved extraordinary metabolic strategies, bypassing traditional photosynthesis by harvesting chemical energy through extracellular electron transfer (EET).

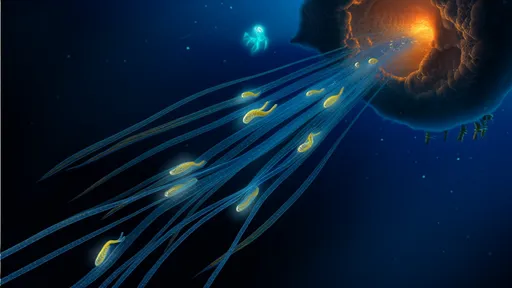

Recent studies reveal that vent microbes form conductive networks resembling miniature power grids. Certain species of Archaea and bacteria grow nanowire-like appendages that can span micrometer distances, creating biological circuits that shuttle electrons between cells and minerals. This direct interspecies electron transfer (DIET) allows microbial communities to collaboratively metabolize inorganic compounds, with some organisms essentially "breathing rocks" by using iron or sulfur minerals as terminal electron acceptors.

The scale of these microbial electrical networks astonishes researchers. Dense colonies spanning several square meters can function as integrated bioelectric systems, with current flows comparable to semiconductor materials. Scientists measuring electron transport rates in vent microbes found conductivity levels approaching those of synthetic conducting polymers. This challenges our fundamental assumptions about biological electron transfer, traditionally thought to occur only across short distances within cellular membranes.

Perhaps most intriguing is how these microbes maintain such efficient electron transfer under extreme conditions. Analysis of their cytochrome proteins shows unique structural adaptations that stabilize electron transport chains against high temperatures and pressures. Some species employ conductive mineral nanoparticles as "biological wires," while others secrete redox-active enzymes that form conductive biofilms. These adaptations suggest evolutionary solutions to problems that human engineers still struggle with in extreme environment electronics.

The discovery of these microbial electrical networks has profound implications beyond basic science. Researchers are investigating applications ranging from self-repairing biobatteries to pollution remediation systems that could harness these microbes' ability to process heavy metals. Some vent microbes demonstrate an extraordinary capacity to extract electrons from toxic compounds like arsenic or mercury, potentially offering solutions for cleaning contaminated environments.

As exploration technology improves, scientists are discovering even more complex electrical interactions in deep-sea ecosystems. Certain vent microbes appear to form symbiotic relationships with larger organisms like tube worms, essentially acting as living batteries that power their hosts' metabolism. Other studies suggest these electrical exchanges might facilitate communication between microbial cells, hinting at a form of biological "internet" operating through electron flows rather than chemical signals.

The study of deep-sea microbial electron transfer continues to challenge our definitions of life and metabolism. These organisms have developed what amounts to a completely alternative energetic paradigm, one that doesn't rely on sunlight or organic molecules but instead taps directly into Earth's geochemical energy. As we uncover more about these extraordinary lifeforms, they're rewriting textbooks on biochemistry, ecology, and perhaps even the potential for life elsewhere in the solar system.

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025